“…. the good deeds of women seldom live after them.” —Unknown

One of the most exciting moments in being a researcher is the beginning — finding all those initial facts. Building a family tree and creating a foundation for all future research is thrilling. I honestly find joy in every detail, every find. But not everyone does. Bear with me, you have to have a strong foundation to build upon Josie’s story. Understanding her family, her community and the events surrounding her are essential. Her life, in basic fact, fell into place relatively easily. She gave me SOME challenges, but we’ll talk about those later! With the first click of my mouse, Josie moved me. However, it is the enormity of her story that continues to push me forward.

Josephine “Josie” English was born on November 28, 1875 (or 1876) in Holly Springs, MS to Berry and Eliza English, former slaves. Josie was the oldest of two daughters born to the couple. Their marriage being a second marriage for her parents, both coming into the relationship with children of their own. Berry was a successful carpenter. He was born in Kentucky and spent a good deal of his enslaved life in Mississippi. His children, along with his first wife, were all born in Mississippi before the war. Some time after emancipation, Berry moved his family to Gallatin, TN. In 1870, the English family was living in the 5th Civil District of Sumner County, TN and consisted of Berry, 52 years old and a carpenter, Julia, 38, Elnora, 16, Green, 14, Rebecca, 12 and Frances, 9. The entire English family were designated as “mulatto” by the census taker, which would logically indicate they were light-skinned.

Julia English died sometime before 1874 and Berry moved with some of his children to Holly Springs, MS. Court records show he married Eliza Pierson [Pierce] on November 11, 1874. After this, the Pierce/English family gets a little mixed up. Part of the fun and frustration of being a researcher is trying to figure out details like which siblings go with which parent over a hundred years later! In 1880 the revamped English family is living in the West Holly Springs Precinct of Marshall County, MS. As listed on the US Federal Census: Berry, a 68 year old carpenter, Eliza, 40, keeps house, Rebecca, 21, Walter, 15, Cornelia, 12, Kittie, 11, Julia, 9, Josephine, 4 and Mary 2. Interestingly, on this census, Berry and Eliza were both designated as “mulatto” while all of their combined children were designated as “black,” perfectly illustrating that race was at the discretion of the census enumerator.

Berry purchased two acres of land on November 10 1880 from Ellen Norfleet and built a home for his family. His home was within close proximity to a freedmen’s school and a good education for his children. This surely must have been motivation for Berry. Both he and Eliza were illiterate.

Berry’s death date is unknown, he died sometime between 1892 and 1900. He lived in Memphis according to the city directory about in 1892 and that is the last documented bit of information found. It does not appear that Eliza moved to Memphis with her husband, however for a brief time, Josie may have. Eliza continued to live in Holly Springs until she moved to Nashville about 1911 to live with Josie. Eliza died in 1915 in Nashville.

Rabbit holes are a constant temptation for researchers. Some people are very focused and adhere to a regimented research plan. I’m sort of a go-with-the-flow human, regimented “anything” doesn’t work for me. I LOVE rabbit holes. I feel as if I learn way more interesting facts from rabbit holes. Researching Josie’s beginnings led me straight to an unexpectedly fascinating little hole. I spent hours….maybe days of researching Yellow Fever. Josie was born just before the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1878 which tore through Mississippi River towns throughout the South, leaving devastation in its wake. Her younger sister, Mary, was born in August of 1878, on the cusp of devastation. Yellow Fever, a virus unknowingly transmitted by mosquitoes, was unmanageable. It affected the kidneys causing jaundice and fever…hence “yellow fever.” Memphis, St. Louis, Grenada, Vicksburg and Holly Springs were among those cities most sorely afflicted. Although today we know mosquitoes transport the disease from one person to another, in 1878 this was yet undiscovered. Scientists knew temperature was a factor and that less cases spread after a good frost. They contributed the disease to “filth and heat.” and it was recommended that citizens sanitize their outhouses.

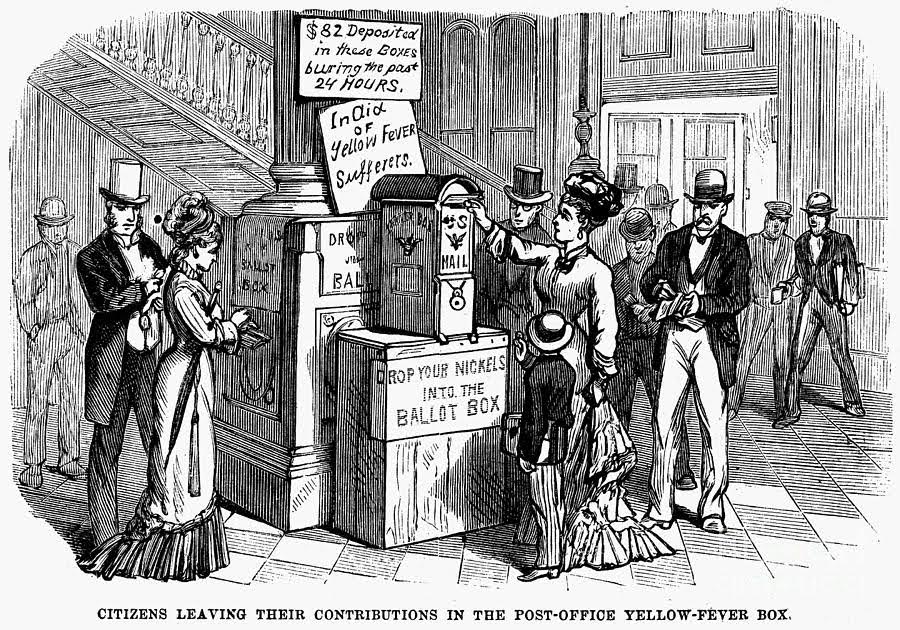

In much the same way people watched the spread of Covid 19 or natural disaster coverage, anxious citizens all over the country watched as daily death tolls were published in newspapers. People watched, helpless to do more than send aid in the form of food, money and medicines, all the while establishing restrictive quarantines. They didn’t want the epidemic to spread. Fear reigned. Relief committees were formed and sent money and supplies along with medical personnel. The outbreak in Holly Springs surprised people because it was not unsanitary. In a report on Yellow Fever in 1879, Dr. Thomas Summers, said Holly Springs stood “in rebuke of all such vain assumptions.” Meaning Yellow Fever didn’t just occur in filth

In Holly Springs the death toll reached over 300. Ida B. Wells (No relation to Josie Wells! And just to note it, my heart FELL when I realized there was NO connection,) who advocated for black rights, women’s rights and was an anti-lynching journalist, lost her parents. The Yellow Fever epidemic killed her father, her mother and her youngest brother within just a few days of each other. Josie was only two years old during the epidemic. Perhaps her earliest memories were of the panic around her. Her parents had a house full of children, one of those a newborn baby. Her father, being a local carpenter, would have been called upon to make coffins for the dead, in the same way as Ida B Wells’ father, Jim, was. Considering the closeness of their homes and their alike occupations, it is highly probable that these men worked together to build coffins for the quickly mounting dead. Quarantines on Holly Springs caused the town to run out of food. Businesses closed down. Those that were able to evacuate, did so. And many of those that couldn’t evacuate, kept dying.

Josie and her entire family miraculously survived the Yellow Fever epidemic.

Chaos and tragedy either brings out the best or the worst in people. While researching Yellow Fever, I found a rabbit hole within the rabbit hole by way of a woman named Annie Cook! Annie was the first in a string of noteworthy women I came across while researching Josie. These women screamed at me for a few lines of recognition. They were voices silenced to our collective memory, or overshadowed by their male counterparts. Annie owned and operated a brothel in Memphis. She was listed in the local Memphis directory as “Mad,” short for “Madam” alongside her location of operation. This was very convenient, not only for her customers, but also for the police officers who on slow crime days, kept arresting her for illicit behavior. The truth is, not many occupations were available to women in the 19th Century. Independence was not always an option for women within “polite” society. So Annie opened a brothel, and secured her financial independence and hopefully her personal independence. Her story is vague, and I was only able to find a basic outline of her life – most likely because she used an alias because of her occupation. Too often we criticize those we feel operate on the fringe of society, criticize their choices. Annie’s story is a lesson in humanity.

As Yellow Fever ravaged through her city, Annie stepped up to the plate. She sent her girls off and Annie opened the rooms of her brothel to care for the Yellow Fever victims. When word of this selfless act got out a letter was received from Louisville dated August 28, 1878. “Dear Madam: This morning’s paper announces that you have opened your house to the sick of Memphis, and that you are ministering to their wants personally. An act so generous, so benevolent, so utterly unselfish should not be passed over without notice. History may not record this good deed, for the good deeds of women seldom live after them, but every heart in the whole country responds with affectionate gratitude to the noble example you have set for Christian men and women. God speed you, dear madam, and, when the end comes, may the light of a better world guide you to a home beyond.” Annie died on September 11, 1878 from Yellow Fever. Her headstone, not erected until one hundred years after her death, read “A nineteenth century Mary Madgelene who gave her life trying to save the lives of others.” The inscription struck me as being so close to Josie’s – women whose lives were so different and yet similar. Annie Cook, took control of her life in the only way she felt was available to her and for that the judgement passed upon her by society would have been overwhelming. And yet during both the 1873 and 1878 Yellow Fever epidemics, Annie, a whore, tended to sick and dying. She nursed them and eventually gave her own life. While affluent “good” Christian people with money and opportunity fled the city. Annie, a member of the lowest echelon of society rose above fear and died because of it. It’s a tragedy that the Annie’s of the world are lost to history. Independent women like Annie, who exhibited unyielding strength and survived in a mans world set the stage for the next generation of women, like Josie. They did this most often without acknowledgement. “…the good deeds of women seldom live after them.”

Love this!! The beginning is so important to the story!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your research paid off! Can’t wait to read more. You have me captivated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a great story. I love that letter. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person