I love my job and I take it very seriously. It is indeed a responsibility I’ve undertaken to make sure the human journeys people had on planet earth are interpreted and taught as honestly as possible. All human journeys. Sometimes urban legend and lore gets in the way of truth and that’s not fair to the people whose stories we tell. It implies their true story isn’t interesting enough. And let me tell you, the Lotz Family don’t need legend and lore. Their true story is interesting. It’s “oh my good gravy, I cant believe he did that” interesting. Just wait!

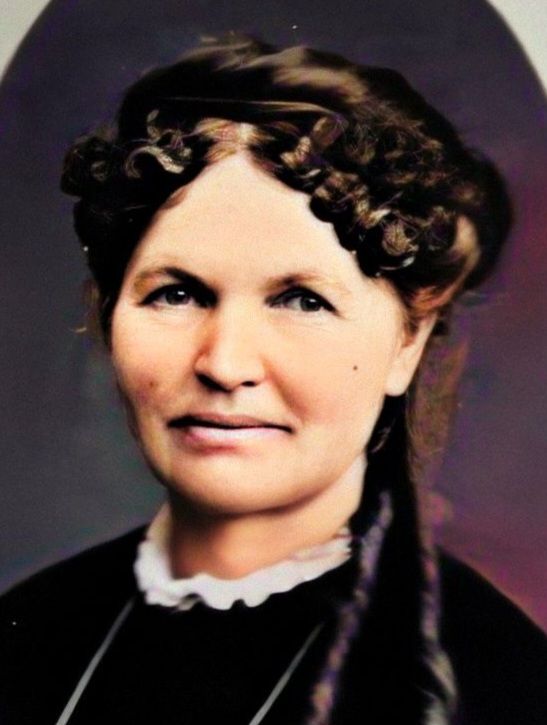

The night of November 30th, 1864 at least twenty-eight individuals took shelter in the cellar of the Carter House as hell broke loose above their heads. The U.S. and the Confederate Armies had slammed into each other mere feet from where they sheltered. The cellar wasn’t the safest option, it was the only option and they had no idea if it was, indeed, safe. Albert and Margaretha Lotz and their children were neighbors of the Carters and were among those huddled together, praying for survival. Many years later, Matilda Lotz, who was a young child at the time, remembered the horrors of the carnage the next day. One of her pet calves had been shot and killed. The sight of the calf, among the dead soldiers and animals stayed with her the rest of her life. This account from Matilda is the only documented memory of the battle from anyone in her family.

The Lotz family were not native Tennesseans. They were like many immigrants who left their homelands to build a better future for their family only to find themselves thrust into the middle of a fight that had been brewing for almost a hundred years. Albert Lotz followed the path of other German immigrants entering the U.S. through New Orleans, travelling up the Mississippi River to various German settlements. The settlements provided a sense of community, security and home for German speaking immigrants. Lotz and his family ended up settling right outside of Cincinnati, OH. There was a piano factory not far from where he and his family lived, which may have provided employment, as he was listed as a “piano maker” on the 1850 census.

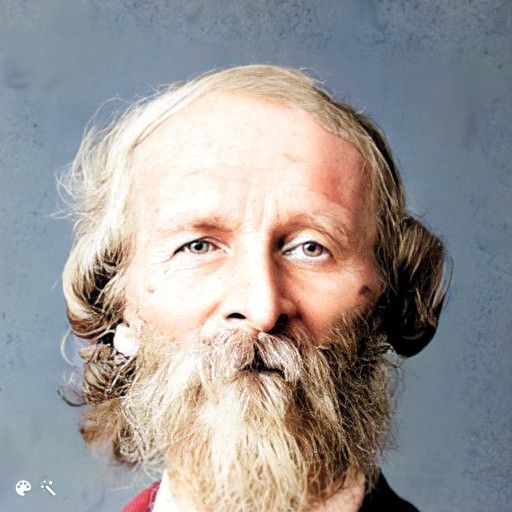

The family’s move to Tennessee came between 1850 and 1853. Albert purchased land and opened up a business tuning, repairing and building pianos. Their two oldest children, Joseph and Amelia, were born in Germany with the remaining three, Paul, Matilda and Augustus being born in Tennessee. Albert Lotz bought property from Fountain Carter and had a house built on the property, in all likelihood hiring enslaved labor to assist with the build. Albert must have been skilled in carpentry, as he built pianos, but it is unknown and undocumented to what extent. His son Paul won a premium certificate at the local county fair for his carpentry skills. The entire family, with the exception of Albert, won multiple ribbons for craftmanship, creative arts and culinary talents.

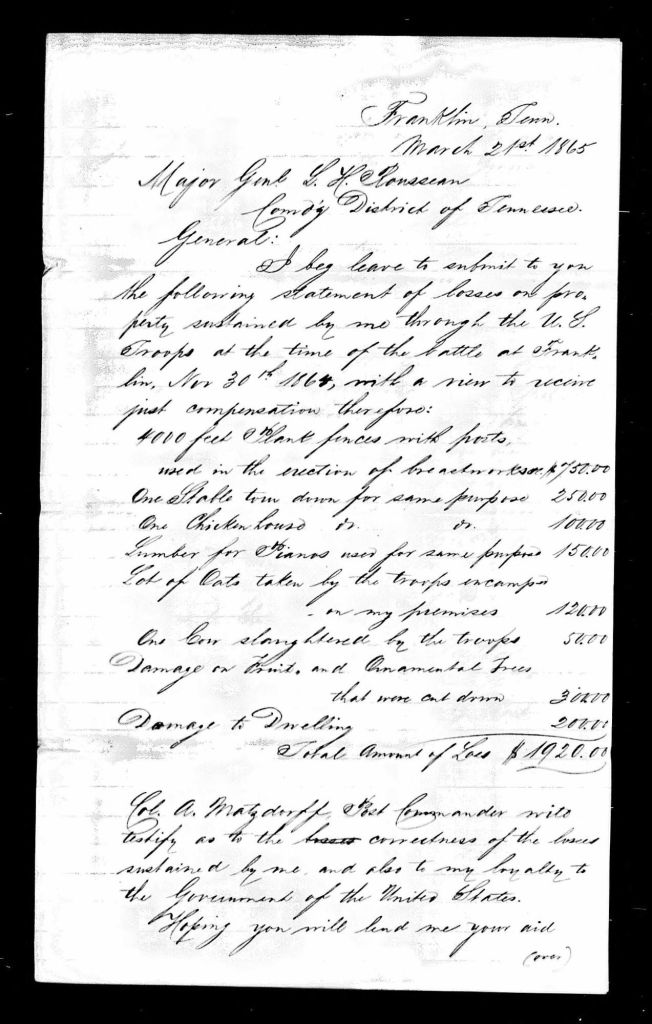

Albert was quite fortunate that a regiment of German speaking US soldiers was garrisoned in Franklin for a part of the war. I can’t help thinking how comforting that would be for a relatively new immigrant. With the referral and aid of one of these soldiers he was able to request a reimbursement for the damages to his property.They were lucky their house suffered minimal damage the day of the Battle of Franklin, only $200.00 worth. Among other requests, the wood Albert had stored for pianos was worth $150.00 and was all confiscated by the US Army.

By 1870 Moscow Carter, whose cellar they sheltered through during the battle, said he went to town and found out the Lotz family had sold up. He hilariously continued “although they aren’t terribly friendly, they don’t offend me much.” Albert Lotz inherited a fortune in California and went west to claim it.

This is absolutely when their new life in America turned into “The Days of Our Lives.” There was so much scandal. I had a delightful time learning their lives. Their scandal is too immense to detail completely, but in short…

Joseph became a county treasurer and had a little issue with embezzling funds into his own account. Apparently, the county gave him money to pay a guard for the county funds and he didn’t think it was enough for a salary, so he kept the salary and bought a lock for the door (I may have laughed out loud at this testimony.) Then there was the time he faced the wrath of the courts for taking one of his brother’s patents and selling it for a profit. Tsk tsk…

Amelia’s jeweler husband was “robbed” and had issues with his story and the insurance claim. Completely understandable, considering the economy of the time.

Paul. Ohhhh Paul. Paul was a charmer. He had multiple talents, but his passion was photography. He was a partner in Elite Photography Studio in San Francisco. He photographed the literal elite in society: actors, musicians, politicians..etc Unfortunately when his photography studio had a flood, Paul did not have enough insurance to cover the damage. Lucky for him he was dating a wealthy young divorcee. Unlucky for her she died “suspiciously” alone in her apartment. But not before she had signed over her entire wealth to her friend, Paul Lotz. Don’t worry, her family didnt let that money just go to a stranger. They fought and he lost. Then there was a great earthquake . His studio was completely destroyed. He lost everything, moved to New York and died.

The youngest two, Matilda and Augustus, moved away from California and escaped the scandal. They were both quite prominent for their positive contributions to society, both in art and invention.

All the while their parents lived out the rest of their lives together. Albert tuned pianos and Maragetha took care of her family.

The Lotz family was intriguing. They were my quarantine project and I had the best time with them. Oh, the screams of joy at finding the photo of Paul! Their story wasn’t what I was expecting. They survived hell the night of the battle. Their survival was a gift, as was the survival of everyone in the cellar. They took that survival and lived vibrant colorful lives. It wasn’t all good. There were scandals and successes. Their truth wasn’t tidy and perfect, but it was theirs. And truth matters.